When we see science fiction stories set during the Victorian and Edwardian eras, the inventor Nikola Tesla tends to show up an awful lot. But the Victorian era and the early 20th century are filled with inventors who led fascinating lives, lives that just don’t tend to turn up in fiction.

Background of top image by John Lemieux.

Some of these inventors’ careers place them firmly in the Victorian era. Others, like Tesla himself, started their careers in the Victorian era and continued to live and work into the 20th century. And while they may not have worked on projects as with as visually impressive results as Nikola Tesla’s publicity photos, they had very interesting lives — and inventions — all the same

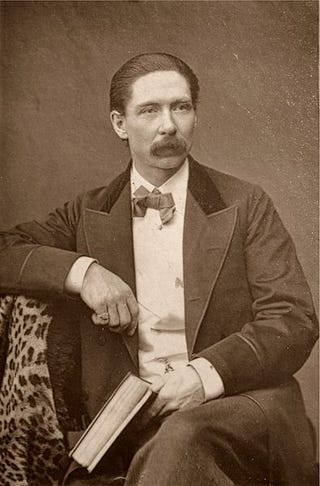

1. John Nevil Maskelyne, Magician and Inventor of the Pay Toilet

Harry Houdini may have the more famous name, but stage magician John Nevil Maskelyne (1839-1917) was also a famous debunker of the supernatural and inventor of both magic tricks and useful devices. Maskelyne got his start as a magician after watching a pair spiritualists known as the Davenport Brothers perform a spirit cabinet illusion. The Davenports claimed that their tricks were genuinely supernatural, but Maskelyne collaborated with cabinetmaker George Alfred Cooke to build a spirit cabinet of their own, which they used to expose the brothers as frauds.

Maskelyne devoted the rest of his career to creating illusions and exposing cheaters and frauds. He famously performed at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly. He invented a levitation illusion. He wrote a book exposing the tricks of card sharps. And, in 1914, he founded the Occult Committee, an organization devoted to exposing fraudulent practitioners of the supernatural. So he wasn’t exactly a Victorian ghostbuster, but he was a medium-buster. He also found time to invent the pay toilet, or rather a lock that would only open if you placed a coin inside.

John Nevil Maskelyne was hardly the only member of his family with a flair for inventing both illusions and practical devices. His son Nevil Maskelyne wasn’t just a magician, but also a rival of radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi. The younger Maskelyne interrupted one of Marconi’s 1903 demonstrations. Before Marconi could demonstrate the ability to transmit Morse code over hundreds of miles, Nevil Maskelyne transmitted a signal of his own, causing Marconi’s Morse code printer to spew out a message accusing the Italian inventor of “diddling the public.”

2. Hertha Marks Ayrton, a Woman Who Fought to Be Recognized

When Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923), born Phoebe Sarah Marks, was first put forward as a possible fellow at the Royal Society in 1902, she was rejected on the basis that a married woman was not considered an eligible candidate for fellowship. During her life, Ayrton was not just recognized for her own scientific achievements; she also campaigned for the recognition of other female scientists.

Ayrton was born in England to an impoverished clockmaker who had fled Poland to escape anti-Semitic persecution, but grew up with educator aunt. Young Sarah Marks learned mathematics and philosophy and eventually attended Cambridge’s Girton College. She took classes in electricity from electrical engineer and physics professor William Edward Ayrton, whom she later married. Professor Ayrton encouraged his wife’s independent scientific and mathematical endeavors. By then, she had already patented a drafting tool called a line-divider, a device ridiculed by some for its simplicity, but which many who used it regarded as magic.

Despite being rejected as a fellow in 1902, Ayrton was the first woman to read her paper before the Royal Society in 1904, an investigation on sand ripples. For her work on sand ripples and the electric arc, the Royal Society also awarded Ayrton the Hughes Medal. As she was being recognized for her own work, she also insisted that other women be recognized for theirs. When journalists failed to attribute the discovery of radium to Marie Curie, focusing instead on Curie’s husband, Pierre, Ayrton wrote in a 1909 edition of The Westminster Gazette, “Errors are notoriously hard to kill, but an error that ascribes to a man what was actually the work of a woman has more lives than a cat.” And that’s all before we get into her work on the Ayrton fan, a device designed to repel poison gas during World War I.

Her name is also interesting. A lifelong agnostic, Ayrton changed her name to “Hertha” after a poem by Algernon Charles Swinburne that was critical of religion. It was a symbolic separation from the Jewish faith of her parents.

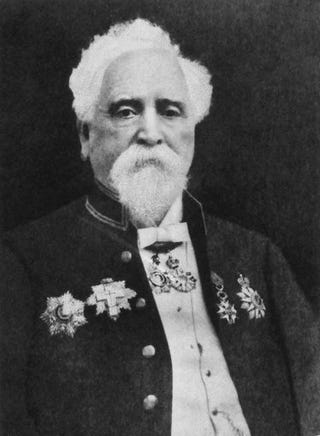

Nikola Tesla was hardly the only inventor who quarreled with Thomas Edison. Hiram Maxim (1840-1916) is one of numerous inventors who, like Edison, laid claim to the lightbulb. But while Maine-born inventor is said to have registered 271 patents in his lifetime, he’s probably best known for his work on the machine gun.

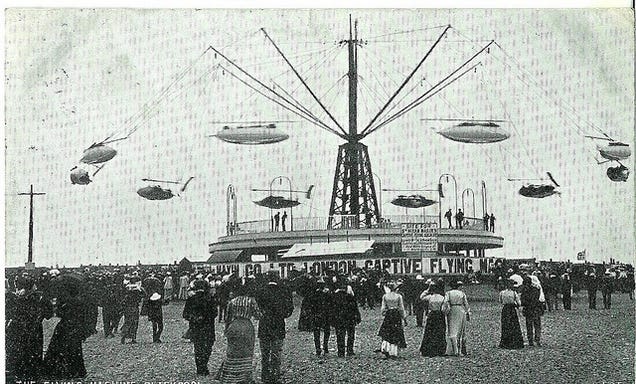

Maxim received his first patent at age 26, for an improved curling iron. The man literally built a better mousetrap (one that automatically reset). He was fascinated by the idea of flying machines, and his research would give birth to an amusement park ride, the “Captive Flying Machine.”

1907 Postcard featuring the Captive Flying Machine, via.

As chief engineer of the United States Electric Lighting Company, Maxim installed many of New York’s first electric lights and fought with Thomas Edison over the intellectual property of the lightbulb (this is leaving out Joseph Swan, who received a patent on his lightbulb in 1880). He moved to England in 1881 to reorganize the United States Electric Lighting Company’s London offices. But he’d eventually become notorious for something far more deadly than electric lighting.

Maxim would later write to the Times of London about the genesis of the machine gun:

In 1882 I was in Vienna, where I met an American whom I had known in the States. He said: ‘Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.

That’s exactly what he did. He developed the Maxim gun, which used recoil to expel the cartridge that had just been used and load the next cartridge. He made that pile of money and received a knighthood from Queen Victoria (although he was actually knighted by King Edward VII). All that for creating a machine of slaughter, just in time for World War I. PBS notes, “Maxim died on November 24, 1916, only days before the Battle of the Somme, where over one million soldiers fell in four months of machine gun warfare.”

His personal life contained its share of intrigue as well. Maxim’s son Hiram Percy Maxim, co-founder of the American Radio Relay League, wrote a book about growing up with his father, A Genius in the Family, that’s supposed to contain rather amusing anecdotes of Maxim household life. The elder Maxim also went through a public scandal when a woman named Helen Leighton accused him of bigamy. The charges were eventually dropped, but not before Maxim was arrested and the matter turned up in the papers.

4. Margaret Knight, the Factory Girl Who Fought a Patent Thief

There are numerous stories of inventors who had their inventions stolen by opportunistic abusers of the patent system, but Margaret Knight (1838-1914) is one inventor who fought back and won. Knight’s formal education ended when she was 12 years old, when she went to work in a textile mill. That’s also when she developed her first invention. After witnesses an accident in a mill, Knight developed a device that would stop the motion of a particular machine if something got caught in it. Her invention made its way into other factories, but at the time neither Knight nor her family members were familiar with the patent process, so she didn’t get to own her idea.

However, Knight would have a formative experience with patent law years later. She was working in a paper bag factory when she figured out a more efficient way of folding and gluing paper bags — one very similar to the same process today. So she invented a machine that could execute her more efficient process. Before she had an opportunity to patent it, however, a man named Charles Annan inspected her machine and filed a patent on it. When Knight learned Annan had a patent on file, she took him to court.

Annan argued that a woman wasn’t capable of inventing such a device, but Knight had, well, actual proof. She had detailed notes that she kept on the machine, and the court awarded her the patent. Knight would go on to develop a number of other inventions, mostly making other improvements on industrial processes.

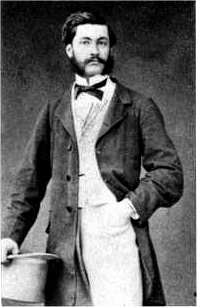

Who invented the moving picture? Thomas Edison and Auguste and Louis Lumière are frequently cited as pioneers of cinematography, but an inventor who gets far less press is Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (1841-1890?). Le Prince’s father happened to be a friend of Louis Daguerre, and Le Prince learned about the chemistry and technology of photography at an early age. He eventually moved to Leeds, where he joined a brass foundry firm, married, and founded a technical school of art with his wife.

Le Prince eventually moved on from the foundry firm and began working on motion pictures. He registered for an American patent on a method and apparatus “For Producing Animated Pictures of Natural Scenery and Life” in 1886, and the patent was eventually granted. In 1888, he filmed the “Roundhay Garden Scene,” the oldest surviving film:

In 1890, Le Prince and his wife Lizzie were ready to take the project public. They planned to exhibit the moving pictures in New York’s Jumel Mansion, but something strange happened before they got a chance. In September, 1890, Le Prince boarded a train from Bourges, France, to Dijon and was never seen again.

There are numerous theories as to why Le Prince disappeared. Perhaps he committed suicide to escape his debts. Perhaps he was murdered by rivals. Whatever happened, no body has been conclusively identified, and the mystery remains.

Norbert Rillieux (1806-1894) was born to a white plantation owner (whose sister happened to be the grandmother of Edgar Degas) and a free black woman in New Orleans. Rillieux was educated, in part, in France, where he attended École Centrale and studied physics and engineering and eventually became a lecturer in applied mechanics.

One of Rillieux’s most famous inventions, however, turned out to be a great boon to the sugar industry in his home state. Some time around 1831, Rillieux developed an improved process for refining sugar. Edmund Forstall, who was building a new Louisiana Sugar Refinery with the help of one of Rillieux’s brothers, learned about the process and invited Rillieux to be the refinery’s head engineer. Rillieux accepted and returned to Louisiana, though his professional relationship with Forstall did not last long.

In the years before the American Civil War, Rillieux’s skills as an engineer were much in demand among Louisiana sugar plantation owners, but he did not receive the same treatment that a white engineer would have. He could install his sugar evaporators at plantations, but he could not sleep in the “big house” with a white family. At one point, he hoped to apply his engineering talents toward the drainage of New Orleans lowlands, but his proposal was blocked by his former employer Forstall. The historian Charles Rousseve claimed that Rillieux’s proposal was rejected because of “sentiment against free people of color.”

Amidst increasing restrictions on free black people in New Orleans, Rillieux returned to France. His interests turned to Egyptology, although he continued to make technical innovations well into his life, patenting a new system for processing sugar beets at age 75.

Okay, this is a really weird story. The Smithsonian Magazine tells the full story of James McClintock, who is perhaps best known for his work designing the H. L. Hunley, the Confederate submarine that became the first sub to sink an enemy ship. (The Hunley also sank. Twice. It’s remains are currently on display in North Charleston, South Carolina, and while it’s a pricey visit, I recommend checking it out if you’re in town.)

The Hunley was laid down in 1863, but McClintock’s strange tale extends far later than that. In the 1870s, McClintock and a couple of collaborators were working on explosive weaponry, and on one fateful evening in 1879, he (apparently) paid the price for his experiments. He and a crew man rowed out in Boston Harbor with a mine containing 35 pounds of dynamite. Shortly afterward, an explosion was heard. The mine had exploded, supposedly taking both man and the boat with it.

The end of the story? Hardly. In 1880, nearly a full year after the explosion, a man visited British consul Robert Clipperton in Philadelphia, claiming that he was James McClintock and that he had been hired by members of the Irish Fenian movement to build torpedos. For a fee, the man claiming to be McClintock offered to sabotage his employer’s torpedos and give working samples of the weapons to the British.

In the end, this man calling himself McClintock pocketed money from both the British government and his Fenian employers, and never provided either with the promised torpedos. He disappeared before his true identity could be discovered. The piece in the Smithsonian examines the possibility

Source:http://io9.com/7-lesser-known-victorian-inventors-just-as-fascinating-1700992149that the real McClintock faked his death only to resurface in Philadelphia, but also suggests that the man may have been one of McClintock’s former partners, one of the men involved in his disastrous weapons experiments.

Source:http://io9.com/7-lesser-known-victorian-inventors-just-as-fascinating-1700992149that the real McClintock faked his death only to resurface in Philadelphia, but also suggests that the man may have been one of McClintock’s former partners, one of the men involved in his disastrous weapons experiments.

No comments:

Post a Comment